UX Magazine

UX Magazine

UX Magazine

UX Magazine

When people with disabilities can’t access a website like others can, they naturally feel excluded. Given our ever-increasing dependence on technology, no one should feel irrelevant or isolated from technology.

Accessibility is one of those topics that gets a mention but is never actually discussed. But the truth is, the internet is not just for one demographic - it’s meant to be a space that is inclusive for all. But with the current status quo, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

We know that there are still populations out there that have difficulty accessing the internet. The most recent census data shows that 56.7 million Americans have a disability. This includes 8.1 million who have visual impairments, 7.6 million with hearing difficulties and 893,000 who could not grasp objects, which could mean difficulties navigating a computer mouse or using a keyboard.

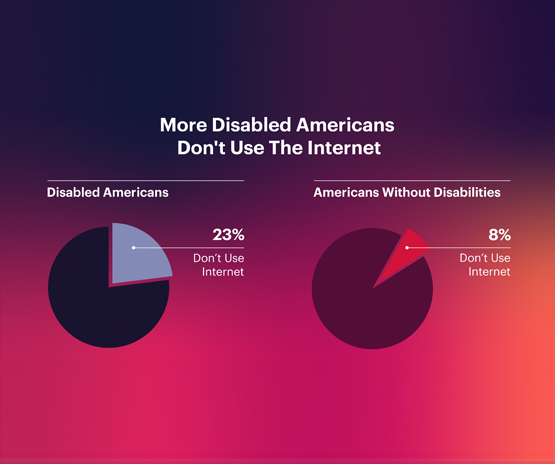

Negative online experiences can be discouraging, to say the least. The Pew Research Center shows found that disabled Americans are less likely to go online — 23 percent report they do not, compared to 8 percent of those without disabilities. Fifty percent of disabled Americans say they use the Internet on a daily basis, far below the 79 percent of those who do not have a disability. Just 39 percent of those with disabilities say they are confident in their abilities to use the Internet and communication devices, according to Pew.

"Leaving anyone behind is a problem. No one should feel irrelevant or isolated from technology."

Basically, they’re being left out of the conversation. People who are blind or have other visual impairments use braille displays or screen readers, software that uses a speech synthesizer to speak the text displayed on the screen. Some sites are incompatible with screen readers. And graphical user interfaces are often retrofitted to work with screen readers as an afterthought. The result is a poor user experience.

When people with disabilities can’t access a website like others can, they naturally feel excluded. Given our ever-increasing dependence on technology — including the meteoric rise of e-commerce and being constantly plugged in through smartphones — leaving anyone behind is a problem. No one should feel irrelevant or isolated from technology.

In 2018, 2,285 federal lawsuits were filed over web accessibility, according to UsableNet. That is a leap from 814 the previous year, a 181 percent jump. Among the industries most affected are retail, food service, travel/hospitality, banking and entertainment. The health-care industry has been affected as well. Healthcare Weekly detailed four health-care websites that were targeted with lawsuits.

Domino’s was sued by a blind man who wasn’t able to place an order on the pizza chain’s website and app. Target and Hulu have settled similar suits. On a smaller scale, the Avanti Hotel in Palm Springs, California, was sued. According to The Los Angeles Times, it would cost $3,000 to make the hotel site ADA compliant, but the lawsuit sought damages for the plaintiff, which could then cause costs to skyrocket in a settlement or in a trial.

These costs are significant, all the more reason for businesses to take stock of their accessibility. Thankfully, the introduction of conversational AI can help to make this a seamless transition.

Conversational UIs are a major upgrade in how we interact with technology. Just as the early days of computing now seem ancient — like the evolution from DOS to Windows, and how pointing and clicking replaced memorizing commands — conversational UIs are a next step forward.

A central component of this is natural language processing, a computer’s ability to analyze and interpret textual or auditory language. Anyone who has interacted with a virtual assistant (Alexa, Siri, Cortana) has experienced forms of NLP/NLU that somewhat scratch the surface on capabilities for this stuff. Chatbots, the pop-up messaging and voice conversational applications used to engage with customers on websites, in apps or messaging services, are familiar examples of text-based conversational applications. But like Alexa, Siri, Cortana and the lot, most chatbots also offer narrow experiences that barely scratch the surface of what’s possible through text-based conversational AI applications.

The AI involved in conversational UIs has the potential to be an even larger disruption, and also opens the door to being more inclusive. Conversational AI platforms built by companies like IBM, OneReach.ai, Microsoft, Amazon, and others (see our breakdown of Gartner Research’s 2019 list of platforms) give companies and individuals the ability to design fully functional conversational experiences, some requiring less coding or even no code. Automated functions require less work for businesses to create — freeing up people to take on more important tasks — and can decrease costs.

Conversation is a natural way to interact with others, and now the same is true with machines. Companies can spare themselves the financial dangers of lawsuits — which can reach multimillion dollar figures for large companies — by moving toward conversational UIs.

Not only is that good for people with disabilities, but also beneficial for those who have less technical expertise. Learning a UI is like learning a new language, and for many, that’s a difficult prospect.

It’s not a daunting task in conversational UIs, because the user doesn’t have to learn the language of the machine. The machine understands the language of the user. That is a monumental shift in human-to-machine interaction. The technology is here. Awareness and accessibility should follow.

By taking action and moving toward accessibility through conversational UIs, companies do right for their customers and their bottom line.

Nick Winkler

Nick Winkler